Matson Helping Lead Improvements in Lithium-Ion Handling

Matson Helping Lead Improvements in Lithium-Ion Handling

In the four months since wildfires tore through the historic town of Lahaina on Maui, government crews, local experts, and Matson employees have been working on the cleanup process, most importantly the handling of lithium-ion batteries and other hazardous materials (HAZMAT).

“HAZMAT is being shipped in sealed drums, and we’ve already moved five of the tentative thirteen, 40-ft containers of above-ground materials, such as paint, oils, insecticides, etc., to the mainland,” said Buzz Fernandez, district manager, Maui. “Containers are shipped from Kahului to Tacoma where we’re working with a local waste management service provider on the disposal process.

“There’s still a lot of work to do,” added Fernandez. “We have four open-top containers being used by cleanup organizations for collecting the lithium-ion and various other batteries.”

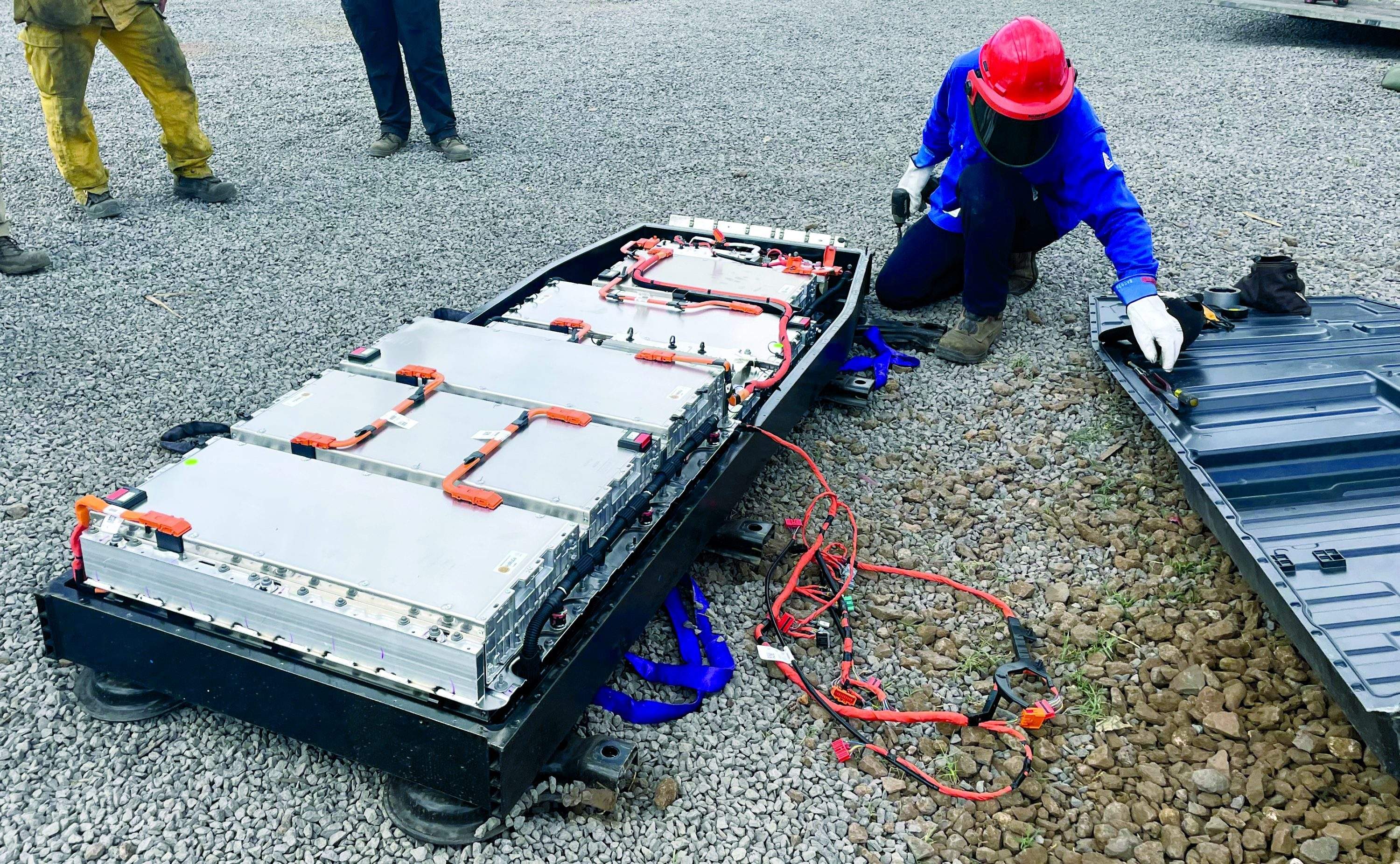

Dealing with lithium-ion electric and hybrid car batteries quickly became a priority for the EPA. Nearly 100 electric or hybrid cars were destroyed in the fire in addition to nearly 300 residential battery energy storage systems, which are used to store excess solar energy.

Energized batteries can potentially catch fire and go into “thermal runaway,” where the battery cells short-circuit and become incredibly hot, creating a fire that is difficult to extinguish.

“This is the first time a natural disaster response has specifically called out in our assignment to address lithium-ion batteries,” said Eric Nuchims, deputy incident commander for the EPA’s Maui Wildfire Response, in a statement to the Honolulu Star-Advertiser.

Removal and transportation of extracted batteries is done by a team of trained HAZMAT responders familiar with vehicle manufacturers, models, and mechanical and battery technology.

Greg Jenkins, Matson dangerous goods specialist and retired captain of Maui Fire Department’s HAZMAT Response Unit, was asked to work with the EPA site team to manage the cleanup of hazardous materials. Greg’s work with the EPA as a subject matter expert was to develop procedures for handling the shipment of hazardous materials and lithium-ion batteries in particular.

It was at Greg’s insistence that the risk of lithium-ion battery fires be eliminated or greatly reduced as a condition of Matson agreeing to transport the materials to the mainland.

“Understanding the potential danger inherent in these materials, we would not OK them for transport on our vessels without the assurance that they could be transported safely,” said Jenkins.

Recognizing that a better understanding of how lithium-ion batteries worked and the risks associated with damaged batteries was needed, Greg worked with the EPA team to conduct various experiments to determine a process for eliminating fire risk. They discovered that by placing them in a de-energizing brine/salt solution before crushing them with heavy equipment rendered them safe for transport to off-island recycling facilities.

The work that is currently taking place on Maui will likely result in changes to future regulations on the handling and transport of lithium-ion batteries. “What we’re learning will benefit the entire shipping industry,” stated Jenkins. “This incident has allowed us to learn how lithium-ion batteries behave in different states of condition, whereas before it was all theoretical.

“We’re dealing with things that have never been done before. Because we’re in a disaster setting, the EPA has been able to do what is environmentally prudent and safe in a timelier manner, something that would be far more difficult and cost-prohibitive in a non-disaster setting. So, in a sense, we’ve been given the master key to gain the access and resources needed to solve the lithium-ion render safe procedures.

“The federal government is now laser-focused on how to handle lithium-ion,” Jenkins continued. “The EPA briefings specific to Lithium-ion Battery Mitigation that the team has been working on have been briefed up the chain of command all the way to the White House. But in many ways, they will be looking to our industry to develop more and better lithium-ion shipping safety procedures. Regulations aren’t enough anymore. We in the industry need to move beyond the regulations and determine what the best practices will be going forward.”

Matson has been at the forefront of this movement, having already been developing tools to eliminate or reduce lithium-ion fire risk, including increasing the spacing between electric or hybrid vehicles on our RO-RO vessels and improving our firefighting techniques and equipment, such as the addition of new fire blankets that immediately isolate toxic gases and smoke, and the Viking HydroPen, a firefighting tool designed to extinguish container fires from the inside. The ongoing efforts to pursue better science will further improve our acceptance procedures for new and used lithium-ion, increasing the margin of safety for Matson personnel and vessel crews.

“Another plus that will likely come from the creation of new regulations and better safety standards is the potential for cost savings related to Matson’s insurance premiums,” added Jenkins. “When the risk is reduced, premium costs drop or at least don’t rise, which means we avoid higher costs that would ultimately need to be passed along to our customers.”

Reflecting on the past months on Maui, Jenkins said. “The EPA specialists have been great to work with, and I’ve appreciated both their attitude and expertise. It’s not always easy working with huge teams as warranted by this situation, but everyone has shown the utmost professionalism and we’ve been able to accomplish a lot in a short amount of time. Formalities are set aside because we’re all working towards a common goal.

“It’s been a pretty amazing experience working through this process,” said Jenkins. “Working a crisis in real-time from the beginning, you get to see the ball moving forward each day. It’s exciting work.”